Seen or Screened? On Platforms, Power, and the Visibility Trap

There’s more than one way to disappear under a spotlight.

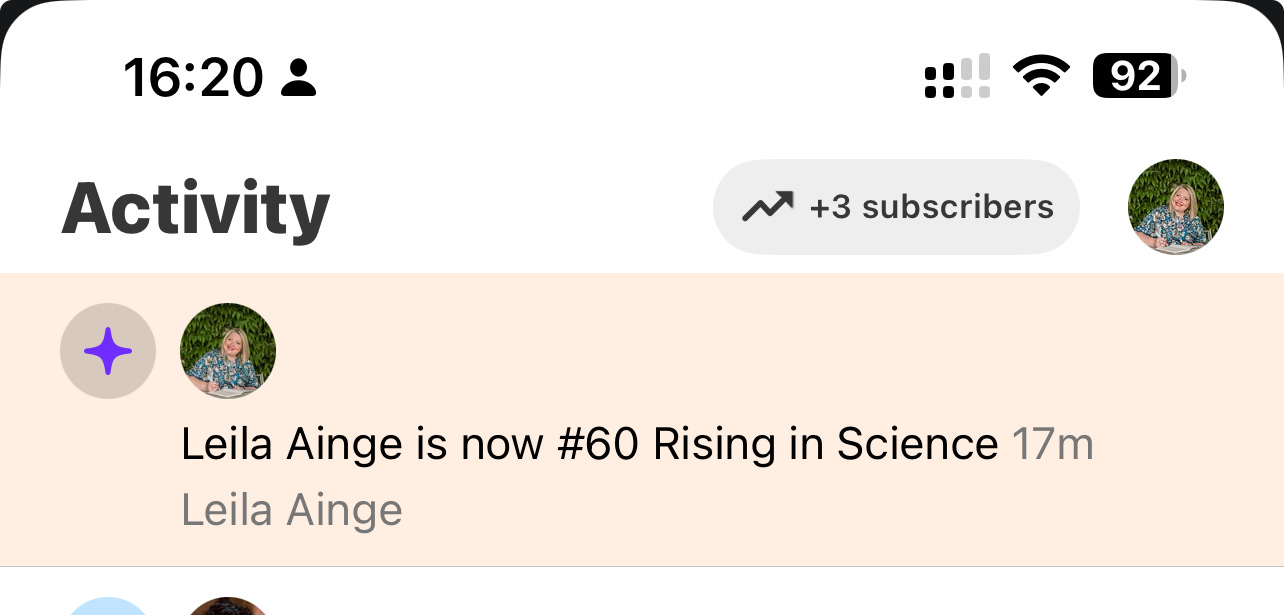

There’s a leaderboard on Substack. You can be a “rising” writer in your category. I didn’t know this until I was notified yesterday, I saw my name , and it lit up the part of me that’s still at school and desperate to be picked first. I told my husband - he’s not *on* substack so his reaction was grounding - ‘what does that mean?’.

Indeed, what does it mean? my inner monologue went like this… so much… psychologically it means so much to me. I would have to tell people who will get it and blog about it and how would I do that without bragging, and what if this isn’t as exciting as I think it is and my bubble bursts? Oh grief, I need to hype myself.

Substack sells itself as a space for sincerity, we write what matters, we share our voice. But tucked into the back end, there it is a ranking system, a popularity chart to remind us that visibility still runs on metrics.

That’s not a complaint, I study the psychology of identity and imposter experiences, and what I’ve found is that many of us, and especially folk with marginalised identities , don’t just fear failure, we fear being seen in the wrong way. Too much, too soon, the wrong crowd. That tension? That’s what I call the visibility trap in my Imposter Phenomenon research.

It’s not about insecurity or a lack of confidence. It’s fulled by something called context collapse.

Episode 2, Season 1 of Psychologically Speaking Podcast covers context collapse and the Imposter Phenomenon, you can find the podcast on all the usual platforms and at www.leilaainge.co.uk/podcast

Context collapse, as Marwick and Boyd (2011) describe it, is what happens when we speak in front of multiple audiences at once, and it’s a modern phenomenon of Linkedin, Twitter/X, Facebook.. substack etc. Your old manager, a university peer, the parent of your child’s classmate, a stranger who found you through a share. You know they’re out there, but you don’t know which version of yourself they’re seeing. So you start writing for a blurry crowd instead of a person. A crowd that might not like what you have to say.

That’s the exhaustion we often mislabel as overthinking and imposter experiences.

A study published this month by Zinn, Roberts, and Oyserman (2024) suggests that switching between our identities, and in my case ,writer, parent, feminist, scientist, psychologist, researcher doesn’t actually cost me cognitive effort (yup, I read the study four times because I am a poster girl for mental load) Their study shows the strain is more of an emotional one, because there is a psychological lag between who we are and who we are showing up as in front of an imagined audience who may or may not clap at the performance.

Context collapse, imagined audiences and now jet lag for the brain, great.

I described this in a note this week as the lag time we need to get ourselves ready to sit and write, the way we use rituals, not so they prepare us, but so they position us. Think of it like stretching before a race you already know how to run.

So let’s take a look at the biggest visibility circus out there. Cannes Film Festival with it’s red carpet is the most glamorous version of visibility with an oxymoron, don’t pose and keep the flow, this is not your limelight this is ours.

The red carpet, I didn’t realise until I looked it up this morning, likely traces back to ancient Greece and the origin story is intruiging and curious for how we think of self promotion and visibility. The red carpet features in a greek play with a hero by the same name, called Agamemnon (it means resolute or steadfast), and the carpet, which is actually a luxurious crimson tapestry is laid out by his wife after he returns from the Trojan war, it is a symbol of status and impending doom in the play. According to various internet sources Agamemnon hesitates because he is aware it will look like excessive pride, but he walks the carpet anyway. I’m not going to add what happens next as you may want to add this to your TBR pile, it’s certainly going on mine!)

The point of a greek play to this essay is that the desire and reluctance to be seen, celebrated, ranked, rewarded is not a modern phenomenon. Just like Agamemnon, some of us still hesitant about stepping onto red carpets.

It is built entirely for visibility, but the Cannes red carpet now comes with rules about how not to be too visible. This year, presumably due to recent red carpet events and decency reasons, the organisers issued a dress code: no nudity, no voluminous gowns, no disrupting the flow of guests. This rule didn’t sound like etiquette though, It sounded like control.

Women are wearing invisible clothes on the visibility carpet. On the surface, it looks like agency. A sheer dress as a statement, but if we step back it’s murkier. Bianca Censori, wore a see-through outfits on a red carpet recently. She didn’t speak, she stood still and the moment went global and viral, some said it didn’t read as fashion, it read as a woman on mute, as a woman to look at, the audience were left wondering is this someone in control, or under control?

Objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) explains this well. Women, especially those under the public gaze, are often taught to see themselves through imagined eyes. You learn to manage your visibility before you’ve had a chance to shape your voice.

The result? You end up trying to be visible just enough. Enough to be relevant. Not enough to be ridiculed.

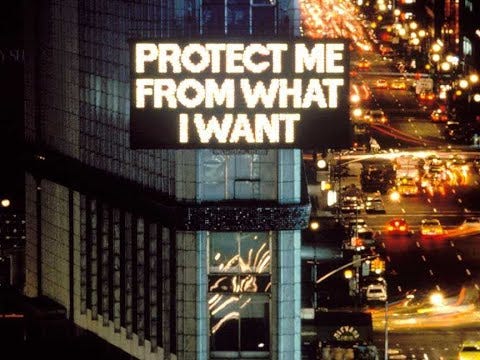

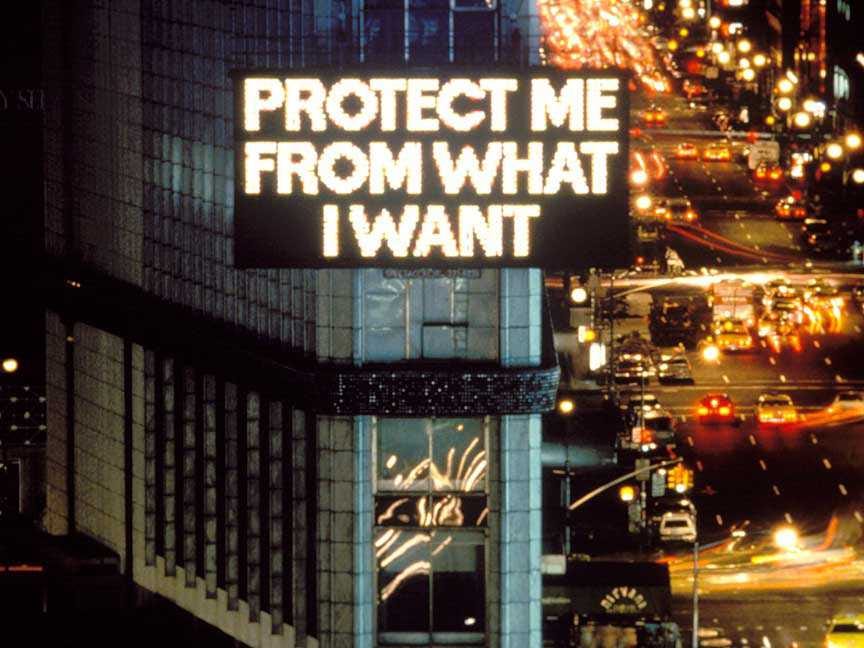

It’s the kind of tension Jenny Holzer captured decades ago in her now-iconic Truism: “Protect me from what I want.” Her work is still pasted across gallery walls and LED billboards, but it reads like a whisper from inside the algorithm. Holzer’s feminist stance used public language to expose how control hides in plain sight. In a visibility economy, that truism lands hard, because we want to be seen, heard, recognised. But we also want safety, control, privacy. Holzer doesn’t resolve the contradiction, she just makes sure you see it in bright lights. That same push-pull shows up in our online lives. Platforms like Substack, LinkedIn, Instagram, they invite you to show up, but they set the terms and you bring your voice. They decide what success looks like, what growth means, what kind of visibility gets rewarded.

from Survival (1983–85), 1985

© 1985 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Photo: John Marchael

And you start to notice it. The language: “top in category,” “most shared,” “rising writer.” It felt personal, but these things are are built into the system. I wasn’t craving that attention until yesterday, but the notification and the structure is designed to keep me hoping for it. And why not? when the system seems to say yes, it stirs something deeper than ego.

I was not so quietly thrilled to see I’d hit #60 in Substack’s Science category. I was really loudly chuffed, and insisted that my husband ‘look at this'!’ ( he tried failed to understand if being placed 60 is good or bad by looking at my facial expression) Of course it meant something to me, it’s a signal that I wasn’t just writing into the void. Maybe I did belong here, after all.

And, I know, there are dozens of these categories, (think modern day school races where everyone gets a medal) enough to make you feel like you’ve found your lane, even if you didn’t win the race. That’s the clever part the illusion of access, spread wide enough for everyone.

It reminded me of another moment that mattered but also gets judged by others: when my podcast was shortlisted for an International Women’s Podcast Award. I put myself forward, as many people do. But it was still judged externally. That line in the shortlist email still makes me smile and I have used the phrase ‘award nominated’ liberally. To some, this nomination is me playing the game, paying to play I should add. My view is why not?

That’s the imposter phenomenon tension. You show up, try not to be too much, try not to vanish and hide behind a rock when it feels too much, yet when something sticks, you wonder: was it luck, merit, or just good optics? You hesitate just like Agamemnon before enjoying it, you want someone to Save you from what you want, god forbid a brag or you get it wrong.

We talk a lot about visibility in spaces like this, and I don’t think we just want to be seen. I think we want to be recognised for what we meant to say which is where the loss of control and context collapse is psychologically rich

However, every now and then, the system you want to be in (and occasionaly saved from) blinks and says yes.

So what does this mean, practically?

Visibility is rarely neutral, it’s shaped by the systems we're part of platforms, dress codes, algorithms, even compliments. And when we’re told it’s our choice, we forget to question who built the stage, or why the lighting’s always a little harsh.

So here’s what I’m sitting with, and what you might want to try:

If you feel uneasy being visible, it might not be you. It might be the structure you're being seen in. That’s not imposter phenomenon.

Would I write it differently if I pictured one kind reader, instead of a row of judges?

Choose your metrics, yes, substack has leaderboards. Instagram has views. Your inbox or whatsaap might have a quiet thank-you. Which one are you letting count?

And if it helps, yes, I feel weird celebrating small wins too but I didn’t want to let this one pass by, I’m holding space and I’m taking my own flashlight to the substack orange hashtag that says 60 in Science and rising. Just don’t expect me to tell you when I’m no longer there.

References

Ainge & Newman (2022): My research explores the experiences of women entrepreneurs with impostor phenomenon in online communities, highlighting themes like the "visibility trap" and coping with comparison

Bravata et al. (2019): This systematic review examines the prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome across various professions. It highlights the widespread nature of impostor feelings and discusses potential interventions.

Clance & Imes (1978): This seminal paper introduced the concept of the "Impostor Phenomenon," focusing on high-achieving women who, despite evident success, struggle with internal feelings of fraudulence.

Fredrickson & Roberts (1997): This article presents Objectification Theory, exploring how societal objectification can lead to mental health risks for women, including anxiety and body shame.

Goffman (1959): In "The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life," Goffman discusses how individuals perform roles in social settings, a foundational text in understanding self-presentation and identity.

Leary & Kowalski (1990): This literature review delves into impression management, examining how individuals attempt to control the perceptions others have of them.

Marwick & boyd (2011): This study introduces the concept of "context collapse" in social media, where diverse audiences converge, complicating self-presentation.

- (everyday): This awesome human encourages hype

Zinn, Roberts, & Oyserman (2024): This recent study investigates identity switching, suggesting that individuals can effortlessly shift between identities without cognitive strain.